A mother and daughter riding public transport.

A mother and daughter riding public transport.

When it comes to action on climate change in the transport sector, women and men have different travel behavior. Statistics show that women take more trips every day, but they use less carbon than men. Women tend to walk more than men and use public transport and taxi services more often than men. They often travel with children and the elderly, and they make more frequent, shorter, trips. This, together with less disposable income, shapes women’s transport choices (with more women than men using buses and walking) and results in their average lower carbon footprint. While more research is necessary, a recent study in Sweden concluded that if men travelled as women do, the country’s CO2 emissions from transport would drop by 18 percent. And a study of travel in Germany and Norway found that men can consume between 70-80 percent more energy for transport than women do. In Greece, men can use 350 percent more transport energy.

However, women’s greener travel is likely to change as they earn more money and become more independent. Women’s and men’s mobility patterns will likely converge. And this is important, because without safe and affordable public transport, women will probably switch to more carbon-intensive options like moto-taxis, three-wheelers, ride-hailing services, taxis, and personal cars. For example, in Mexico City, women of a higher socioeconomic status use cars at five times the rate of women with a lower socioeconomic status. And, of course, more women in cars— more people in cars— means a rise in global carbon emissions. And apart from these significant environmental implications, this projection also has social and economic impacts. Women want to move safe and effectively. The public transport available, particularly in developing countries, shows that women can be “captive users” instead of loyal customers.

Planning around decarbonizing transport has largely focused on vehicles and male-dominated travel patterns. As more and more women start joining the labor force and altering their mobility patterns, it is vital to capitalize on their sustainable habits of walking, biking, and public transport. Public transport cannot afford to lose women. In Pristina, Kosovo, 68 percent of regular public transit users are women. In the European Union, that number is also high-- 60 percent of all riders are women (World Bank calculations based on 2015, EUROSTAT, EU 28 population, and 2014, European Commission, Quality of Transport Report). If women stop using public transport in high numbers, lower revenues will lead to worse service, from timeliness to cleanliness to safety, and this will have devastating consequences across the board, including on climate action plans. It makes sense that factoring gender into urban transport is a necessary step on the road to decarbonization. And women do, and will, have choices; they are not simply “captive” transit users. In a recent World Bank study in Serbia, 84 percent of women consider it important that their transport pollutes as little as possible, as compared to 76 percent of men.

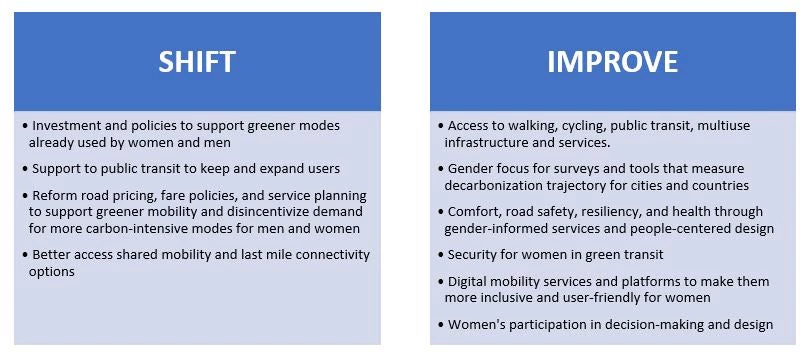

We support the steps below, outlining ways to shift and improve transport practice for stronger climate action with a people centered approach. These steps can help lower carbon emissions.

COVID-19 and public health are also worthy of further study. The pandemic has pulled people away from mass transit. It is vital to get them to re-engage, and quickly. This can be done, in part, by managing women’s specific mobility challenges. This is a core part of pandemic recovery.

This is a clear opportunity for the development and climate agenda. Along with the energy sector, transport can have a significant impact on the green transition, since it currently represents 17 percent of global CO2 emissions (23 percent of GHG emissions) and those numbers are rising quickly.

E-vehicles are currently considered a very important way to decarbonize, but they are not the only solution to the transport decarbonization agenda in the medium term. Acknowledging the role that people-centered and gender-informed policies can play in meeting climate action plans is very relevant for the green transition.

Climate action plans are a way to re-think traditional approaches and shift the focus to users. Transport and energy-efficient policies that do not meet the needs of women ignore a hugely significant group of transit users. Ignoring different mobility patterns for women and men lowers the chances of a successful move to cleaner technologies. Getting transport policies and fuel excises right means factoring in the needs of women, who are currently greener users of transport systems. It is time for a more nuanced, people-centered approach to transport climate action plans.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Lina Mosshammer for her technical inputs.

Join the Conversation